Netflix killed my local video store

And adding a chrome extension won’t bring it back

I miss going to Civic Video on quiet Friday nights with my mum and sister. A New Release was a rare treat; my parents were keen to teach us you can't always get what you want in life, unless what you want is a Weekly rental. I can still conjure the smell in my mind – that distinct combo of plastic, feet and popcorn that so captures the early 2000s. Anyone confused why world governments can't agree on anything has forgotten how hard it was to choose a movie the whole family, including dad, would stay awake through. God bless Johnny English.

Streaming and social media have dialled this challenge up to eleven. Endless content floods our living rooms and we’re no longer bound by mum’s dwindling patience or the 24-hour rental period – those wise constraints that made us free. Instead, we’re trapped by our modern abundance in two seemingly contradictory ways:

Increasingly personalised media – there’s so much good content it’s hard to justify watching something you might not like with your family or friends. Isolation feels worth it to avoid watching Bridgerton, at least at the time.

Increasingly generic curation – the sheer volume of content is overwhelming enough to trigger an existential crisis if you dwell on it too long. Curating becomes exhausting, so it's easier to just surrender to the algorithms designed by Silicon Valley tech bros to channel our attention.

What’s happening to culture?

How can we feel like our social media feeds are getting more personal and also worry they’re getting more generic at the same time? I used to think saying “both can be true” was a cop-out. But it’s not. It’s a way to express when two things that seem in opposition are actually being driven by a shared underlying force.

In this case, what we’re seeing is technology rapidly expanding culture, right before our eyes. It’s worth noting: more content doesn't automatically mean more (or better) culture. Just like rainforests get bulldozed to make way for cash crops, tech can turn formerly rich subcultures into bland monocultures. But that's only part of the story.

Culture, after all, is just humans having experiences. Technological development expands culture by sustaining more human life and enabling each of us to have more experiences. The internet at its best fosters unique, hybrid subcultures that bridge time and distance – like when my grandpa buys vintage car parts on eBay or my cousin finds a supportive community with other gamers online.

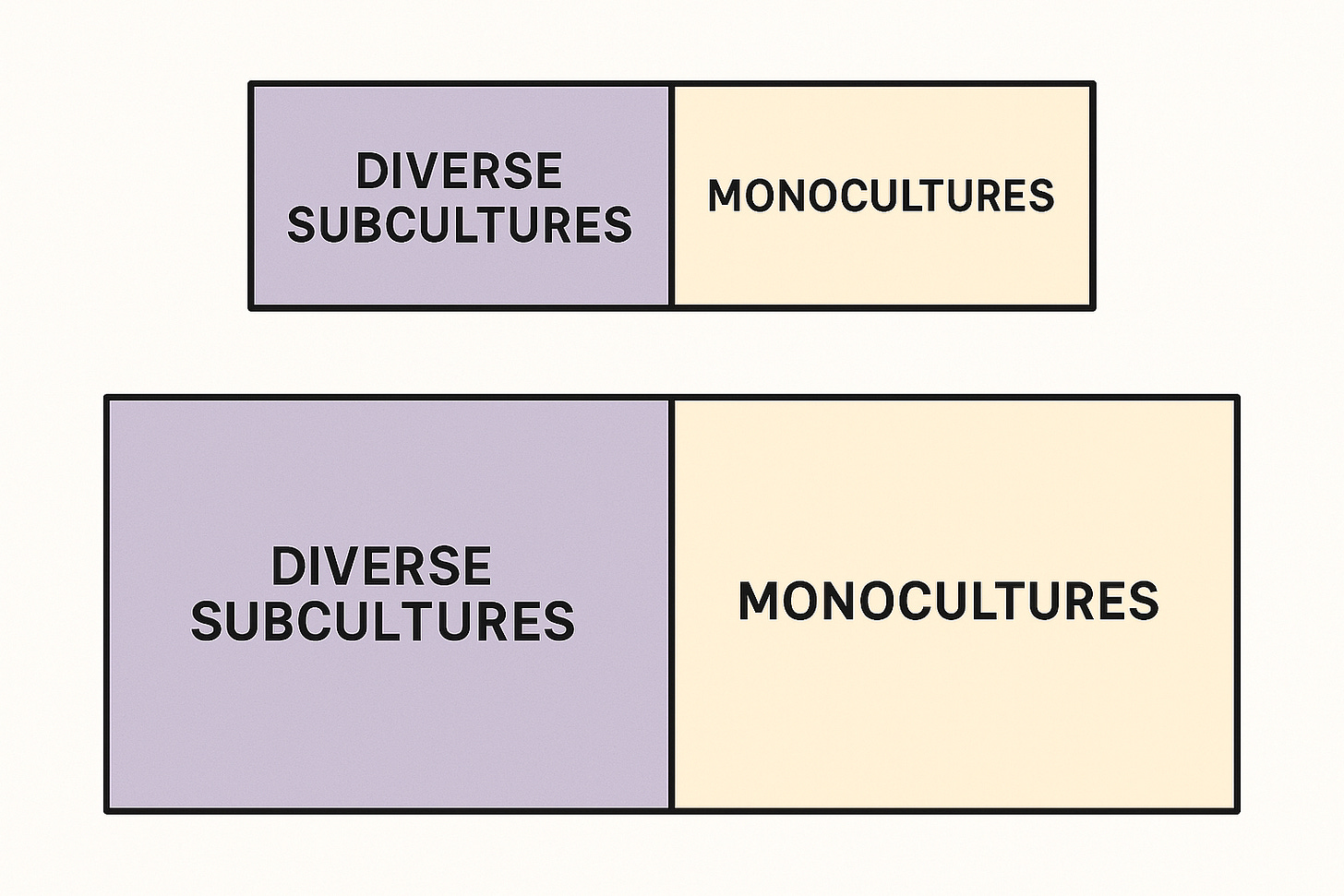

Still, not everything survives cultural evolution. My hometown could resurrect Civic Video if it really wanted to, but for now, I have to accept that it’s gone. Cultural adolescence is messy – some beautiful things vanish, some ugly things spread – but overall, culture grows. Seen this way, it makes sense why this cultural moment feels like everything, everywhere all at once. Technology is creating more monocultures and more subcultures at the same time.

Figure 1: More of everything!

This explains how someone like Chappell Roan could be on track for massive stardom while more people than ever haven’t even heard of her. Or why Marvel movies gross billions yet their superheroes lack the universal cultural recognition of the bespectacled Clark Kent. Interestingly, sports stars seem to buck this trend, having remained household names into the streaming / social media era – perhaps because sport, like religion, is one of the few major parts of culture that still bridges ethnic and class lines.

A side note on monocultures

Now we all love to criticise technological progress for creating monocultures. But we throw around the label “monoculture” far too easily, a deception that betrays our lack of curiosity for what we don’t care to see. For instance, we could easily name a good chunk of the US’s fifty states – even their obscure capital cities, like Toronto. Yet despite China's near-equivalent global impact, most of us would struggle to name even one of its provinces.

We view China from afar as one monolithic terracotta army, while focusing obsessively on America's hyper-individualism, where everyone apparently aspires to become their own Michelangelo sculpture, complete with personal branding. Yet both perspectives distort reality, reflecting an inequality of attention rather than genuine cultural understanding.

Chinese culture has plenty of creative subversion. During Halloween 2022, locals in Shanghai mocked harsh pandemic restrictions by dressing up in hazmat suits and as surveillance cameras. Online forums routinely critique government censorship in subtle ways, using coded language like “rice bunny” (pronounced "mi tu") to discuss issues like the #MeToo movement. And it’s not all main character energy in American culture either – there’s plenty of people happy to just follow the crowd. Before we were grumbling about every kid in America doing the same viral TikTok dances, we were turning our noses up at American families for their McMansions.

Does technology favour diversity or uniformity?

Historically, technology’s cultural impact has been chaotic but rarely catastrophic. The printing press initially seemed to threaten established culture. Martin Luther’s protest went viral, splintering the Catholic Church. Yet today, there are far more Christians (and non-Christians) globally than in the 1500s. After the initial content overload, people adapted and culture thrived.

Evolution seems to handle technological disruption remarkably well. Once a good idea emerges, nature tends to replicate it. But replication also introduces shared vulnerabilities, making diversity crucial. Oil, for example, became so useful that it spread everywhere across the economy, but this dependence now poses profound risks to our planet, forcing us to come up with innovative alternatives to survive.

However, abandoning technology altogether isn’t viable. Anyone who’s watched Alone knows life without tech isn’t glamorous – it’s constant, life-threatening calculations about how much energy to spend building shelter vs trying to find water vs figuring out where your next calories are coming from. Sailing to climate conferences is a powerful political statement against a branch of technological evolution gone wrong, but going back to our roots won’t work. The solution is new branches with better technology. And those branches are where the juicy new cultural fruit will grow.

What’s next for culture?

Effective altruists see Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) – ultraintelligent machines that can design even smarter machines – as culture’s ultimate endpoint. But we’re not even close to that with Large Language Models (LLMs). What we have are incredibly advanced pattern recognition machines that can sift through huge amounts of data and find patterns that a human, even with lots of time, may never notice. Repackaging old ideas in new ways (and saving us all a lot of time in the process) is a novel contribution to culture, but it’s no Einstein.

All the data (and transformers) in the world won’t resolve the tensions between quantum mechanics and general relativity – for that you need new theories. And most artificial intelligence systems are not being designed to develop such theories, imagining their implications and running experiments to explore them. Take OpenAI’s video generator, Sora. It produces realistic visuals by mimicking patterns, not by trying to understand physics. If tasked with depicting beer pong on Mars, it’d need Elon Musk to host a frat party there first, whereas a filmmaker in collaboration with a physicist could take a stab at depicting it for you tomorrow.

Anakin, please come back from the dark side!

Musk, despite resembling Darth Vader more each day, is still shaping our cultural future significantly, beyond just destroying Twitter. He has a unique talent for building physical technologies and destroying social ones, not seeming to get there’s a difference between the people who built America, the Carnegies and Rockefellers, and the people that made America, the Hamiltons and Jeffersons. That blindspot aside, he’s nonetheless at the forefront of two key culture-shifting technologies.

Relative to his other pursuits, Neuralink flies under the radar. Yet we’re destined for more sophisticated brain-computer interfaces than hunching over typing on our phones. For now, the elective brain surgery required to insert Musk’s electrode-laced threads aren’t appealing unless you have a serious neurological issue. But his company has undeniably brought our understanding of the brain’s electrical circuits a long way since One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. Once the benefits become tangible to people, the influence on culture will be massive.

We tend to think of our brains as private places for thought. But a device that interprets our neural signals could conceivably be used to share our thoughts directly with our friends, or even the public. At that point we’re dealing with a while new form of media. And it’s not hard to imagine a market for people’s most intimate thoughts. I’d definitely pay to know what someone thought of me after a first date.

If all this makes doom-scrolling seem harmless, what’s crazier is that we’ll adapt to this brave new world too. Unfamiliar mediums have always scared us. Socrates feared writing would erode our ability to discuss ideas, taking our attention away from the present moment and evermore into the stylus. Sounds awfully familiar to the moral panic over phones.

As our cyber connections intensify, our minds will crave radical disconnection. Sadly planes are no longer the digital detox they once were, but space travel is a different story. Unless we figure out how to communicate faster than the speed of light, chats between Earth and Mars will have a three minute lag, at best. That means no FaceTime with interplanetary loved ones (sad) and no Joe Rogan interviews with earth guests from his new studio across the solar system (extra sad). Instead, adventurers will have to relearn ancient practices, like texting.

That’s what cultural expansion looks like: new mediums, old traditions revived and more strange hybrids. Some people’s thoughts on literally the same wavelength, others disconnected by galaxies.

Culture isn't dying, but it’s getting pretty weird and it’s on track to get even weirder. At least watching people try to date on Mars while their thoughts run in subtitles below will make for cracking reality television. Love is Blind Season 55: Men are from Mars, Women are from Venus. Thoughts sold separately. And if it all gets too much, at least you can always switch off.

The dizziness of freedom: Or how to keep your head from exploding as culture expands

I know I’ve painted a rosy picture of the relationship between technology and culture, but like anyone, I do get overwhelmed trying to keep up with everything that’s happening these days. It’s not easy when culture is expanding and you’re still just one person with one life and an ever-growing Goodreads want-to-read list.

For me, managing tech anxiety is less about what platforms I’m on and more how I’m on them. I don’t use most social media, because Zuck sucks. But even LinkedIn, WhatsApp and email still mess with my head sometimes. Knowing my social life didn’t implode when I deleted Instagram helps. So does getting out into nature.

A year ago, I was on a ferry off the coast of West Sumatra, taking a chance to disconnect and go surfing. Standing on the sun deck, I watched the mainland fade into the horizon, leaving nothing but ocean in every direction. I got bored and went inside, where my friends were watching Jackie Chan's Rumble in the Bronx in the air-conditioned cabin. We got swept up in the 90s nostalgia and even without dialogue, it was incredible. We laughed, we gasped, we didn’t reach for our phones once.

After the movie finished, they started blasting Indonesian music. Most of it faded into the background, but one instrumental track caught my ear. Without my phone, I would've just enjoyed the moment and probably never heard that song again. But thanks to Shazam, I discovered "Arak Iriang" by Eriway and it’s a banger.

Finding a catchy new tune is always great, but looking back the highlight was obviously just the chance to watch a dumb old movie with one of my closest friends on a crazy boat in the middle of nowhere. When it comes down to it, even if the boat captain (or your sister most Friday nights) picks a terrible film, it’s not the end of the world.

Loved this piece!