Learning from the world’s oldest continuing culture

Could Indigenous Australian social technology offer clues for better global government?

I wouldn’t be alive today if it weren’t for two Indigenous guys, Yarri and Jackey. They didn’t save my life, but they did save the lives of some of my ancestors.

Generations ago, my great-greats were given a parcel of land in a town called Gundagai. The area was flood-prone and the local Wiradjuri people warned them it wasn’t safe to build there. My ancestors petitioned the government to help relocate the township, but the governor refused. Then in 1852, heavy rain burst the river banks. The water rose fast, sweeping houses away and leaving families clinging to trees. More than eighty people died – still Australia’s deadliest flood.

It would’ve been far worse if not for Yarri and Jackey, who spent three days paddling a bark canoe through the rapids, rescuing people and taking them to higher ground. They risked their lives saving a bunch of white people who’d taken their land and declared it their own. They may not have conceived of ownership in quite the same way, but it was still their system, their relationship with the land, that was stolen. And yet they responded to this violent act with an act of love.

Down the barrel of a gun

When the United States bombed Iran without seeking UN Security Council approval, I expected a bigger reaction. Instead, the so-called “rules-based order” was shown to be a facade, behind which lurked Mao Zedong’s maxim: political power grows from the barrel of a gun. Whether or not future American presidents decide to respect international law again, the point is one big slip up is enough to break the spell. Like seeing your dad eat the cookies left out on Christmas, it’s hard to go back to believing in Santa after that.

And it forces a question: Has Daddy Trump simply reminded us peace and freedom were always dependent on armies and the threat of violence, or is there still hope it could be otherwise?

Space, trade and peace

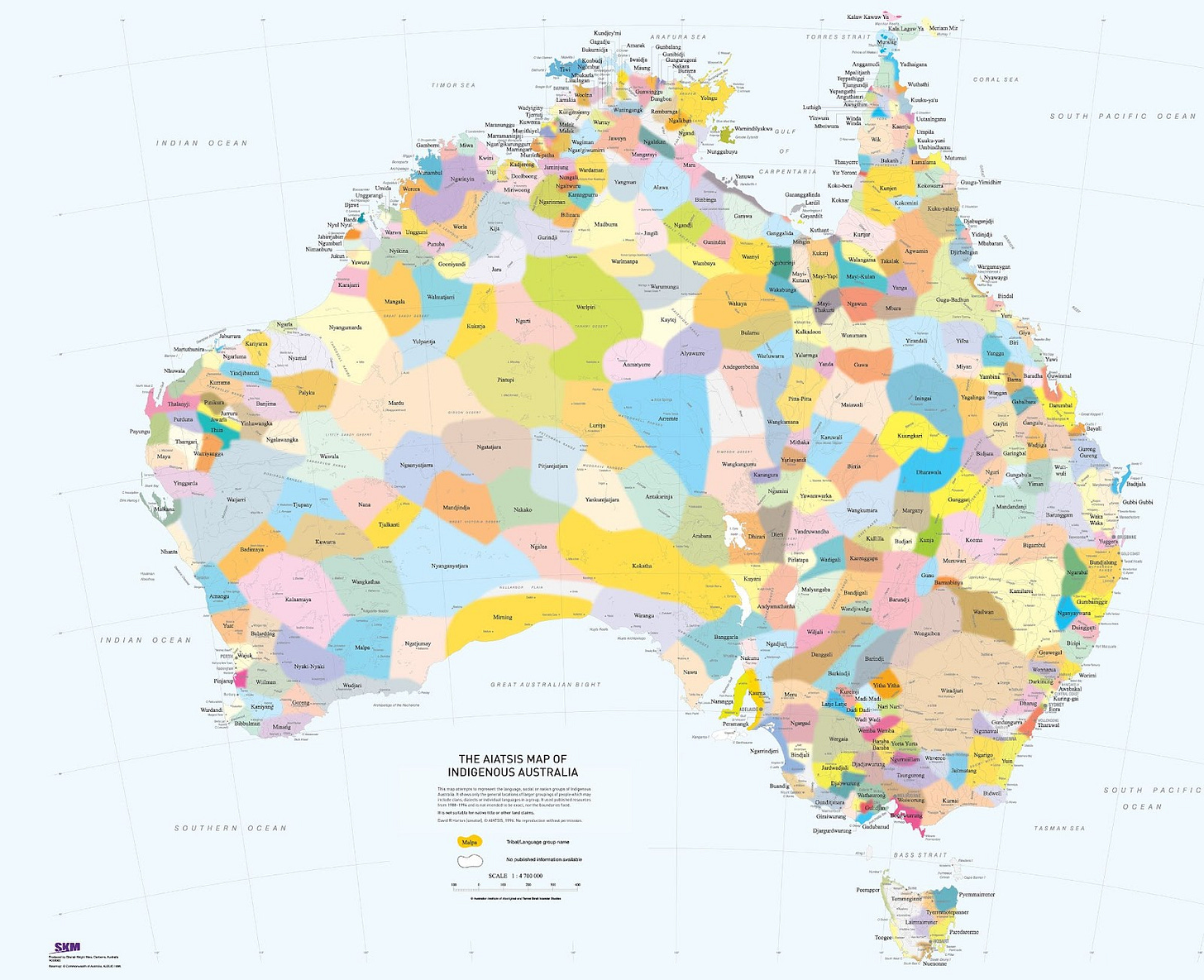

Indigenous Australia gives me hope. At least 60,000 years ago, Aboriginal peoples arrived in northern Australia, likely coming from what’s now Indonesia when sea levels were lower. Within about 10,000 years they’d spread across the continent, from the boundless plains of the outback to the endless beaches along the coasts and all the way down to Tasmania.

Part of the reason they spread so widely was necessity: as populations grew, people followed water and food. But there was another important factor. When conflict threatened, the abundance of land meant groups could split off rather than fight over scarce fertile areas. Over time, this resulted in hundreds of nations each with their own distinct languages and customs; a relatively peaceful system where negotiation, trade and free movement were common, and the constant war-of-all-against-all that marked Europe was not.

Contrast this with Aotearoa (New Zealand). Polynesians arrived there much more recently, around 700-800 years ago. The islands were smaller and less forgiving: fertile land in valleys surrounded by rugged mountains, colder climates and limited supplies of the large sea life Polynesians relied on elsewhere. Māori society adapted with strong warrior traditions, hill forts and more frequent conflict. Not a moral failure, just an understandable response to scarcity.

So when European colonisers arrived down under, they encountered two very different realities. In Aotearoa, Māori military strength forced the British to negotiate, eventually leading to the Treaty of Waitangi. In Australia, no such treaty was offered. The land was declared terra nullius – empty, as if tens of thousands of years of enduring culture had produced nothing of value.

The systems developed there over millennia – community governance, ecological knowledge, oral law, trading networks – were invisible to European eyes. Without forts or weapons to signal power, Indigenous people were dismissed as uncivilised. So much was destroyed. What colonisers wrote off as primitive customs are only now being recognised in economics as sophisticated social technologies: Elinor Ostrom won a Nobel Prize for showing how communities govern shared resources and solve the tragedy of the commons through exactly these kinds of institutions.

Enter game theory

There is an elephant in the room. Yes, Indigenous societies endured peacefully for millennia, but ultimately they were overrun by a stronger power with guns. Surely that proves the point: the only way to protect your freedom is to be able to fight for it. It’s basic game theory: play long enough and eventually a bully’s going to come along and steal your stuff.

But that’s just it, it’s basic game theory. In games that go on indefinitely – i.e. most games in the real world – cheating is usually a bad idea. One way to sustain cooperation is to punish bad behaviour “tit for tat”; wrong me today and I’ll wrong you tomorrow, then things go back to normal. The trouble is punishment isn’t a perfect instrument. One misstep, one overreaction and cooperation unravels into a Godfather-style revenge feud.

Thankfully there’s an alternative to sustaining cooperation through punishment; what Robert Axelrod called “the shadow of the future”. If I expect you’re going to be sticking around for a while, I should probably treat you well today.

The men who saved my ancestors certainly weren’t going tit for tat. By any logic of payback, Yarri and Jackey had no reason to risk their lives for people who’d stolen from them. And yet they did. Christians might call it grace; fans of Carl Jung might call it the spirit of the depths. Either way, they went way beyond the baseline of modern Australian ethics – don’t be a dickhead – and provided a timeless reminder that turning the other cheek isn’t a naive strategy. In the longest game of all, it may be the only way we win.

Dealing with the past unlocks a better future

It’s sometimes argued that dwelling on the injustice of colonisation is unhelpful, that it only deepens divisions in modern multicultural nations. Every country has a bloody, complicated past, and many of the freedoms we now enjoy were secured through force – Hitler was defeated by armies, not meditation circles. Better then to focus on improving the future.

But improving the future is exactly why the past matters. Because for tens of thousands of years, Indigenous Australians sustained hundreds of nations without armies, finding ways to trade, negotiate and coexist relatively peacefully. There was still violence, of course – our standard doesn’t need to be perfection – but far less than elsewhere.

The 20th century’s League of Nations and United Nations both stumbled upon the same problem: global governance without teeth looks like theatre, but with sharp teeth looks like Big Brother. What then does a better future world government look like? After the next major conflict, should we propose the One Earth Government gets their own military force?

Indigenous Australia shows there’s another model: freedom doesn’t always have to be defended by one central institution with a monopoly on violence. It can also be sustained by space, free trade and ways of living that cultivate the deeper human principles that Yarri and Jackey embodied. This isn’t just history – it’s a reminder that societies have other levers for stability besides armies, including the simple ability to step back, choose not to retaliate and if necessary, put some distance between us.

Nowadays, the search for open space is less about moving down the coast to Tasmania, or crossing the Atlantic, but venturing into the stars. Strangely enough, it does seem by the time Elon Musk is capable of going to Mars, he might not feel very welcome on Earth. Still, I’d rather he had the option to strike out to another planet to prove himself rather than fighting for control of the nuclear weapons here.

The space between the stars

Indigenous Australians have a profound relationship with space. Where Europeans mapped the constellations by connecting the brightest stars, Aboriginal astronomers also saw the darkness between them. Out of the Milky Way’s shadows they traced the great emu in the sky – a constellation made not of light, but the absence of it.

It’s a fitting symbol. Our temptation is to assume the future of global governance will require brighter, more violent stars – a bigger centralised military, a consolidated nuclear arsenal. But perhaps the real hope lies along a quieter path, in the space between the stars.

There is no haka in Indigenous Australian culture. The ancient wisdom of non-violence doesn’t yell; it whispers gently through history. Above the light pollution of our fancy cities and the noise of our great power rivalries, the silent emu hangs in the shadows; an enduring reminder that another way is possible, if only we’re willing to look.

Another fantastic piece and perspective that resonates with me so much. Have passed onto my team - I read this after I spent a day in a workshop pulling apart the new HSIE Syllabus where the indigenous perspectives are now imbedded correctly for the first time ever. Cheers, Pete